THE CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Apocrine gland anal sac adenocarcinoma are tumours that develop from the apocrine cells of the anal sacs in dogs. It is a relatively uncommon tumour in dogs, representing roughly 1-2% of all skin tumours, and is rarely seen in cats. Although it is the most common malignant tumour of the perianal region, the AGASACA accounts for 15-20% of all perianal neoplasia. They are locally invasive and metastatic and spread to the regional sub-sacral or medial iliac lymph nodes first, then to the abdomen and pulmonary tissues in advanced stages.

In many cases, these tumours may be suspected or identified in multiple different ways:

- An incidental finding during routine examination is when a mass can be felt rectally or close to the anus externally.

- Licking the perianal area, straining to defecate, and bleeding were the most common signs suggesting the presence of a large mass close to the anus or regional lymph node enlargement in the pelvis/under the lumbar spine.

- Owners noted increased urination and drinking in some patients due to high ionised calcium levels secondary to tumour secretion of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTH-rP). This can be seen in 25% of dogs with anal sac tumours.

THE DIAGNOSTIC WORK UP & CLINICAL STAGING

When this tumour is suspected, a rectal examination is first performed to localise the affected side of the gland(s) at the veterinary clinic. The rectum is palpated dorsally and laterally for the anal sacs and sub-lumbar lymph node enlargement. The differential diagnosis for an anal sac mass includes chronic sacculitis, impaction, hepatoid adenomas (although these are generally in the perianal cutaneous locations) on top of AGASACA. The initial diagnostic test generally includes a transcutaneous fine needle aspirate cytology which will usually rule out the other differentials. However, in some cases, the cytological diagnosis can be complicated by inflammation/infection. Preoperative evaluation should incorporate rectal examination to assess for lymphadenopathy, minimum database (including ionised calcium), and abdominal imaging for staging (and thoracic imaging if indicated), such as an abdominal ultrasound or CT scan.

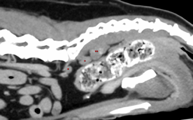

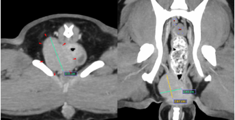

Below is an example of the details of images achievable via CT in detecting metastatic and primary lesion.

Abdominal CT scan of a patient with RIGHT anal sac mass (red arrows) and regional lymphadenopathy along the iliosacral lymph center (red dots).

THE TREATMENT

The goal of the treatment will depend on the stage of the anal sac tumours.

TREATING THE TUMOUR AT THE PRIMARY LOCATION (I.E. ANAL SAC)

SURGERY

Surgical excision is often the first treatment of choice at the veterinary clinic. These tumours should be removed with wide margins, but resection is usually marginal given their proximity to critical neurovascular structures and the rectum. Sub-sacral or medial iliac lymph node resection is performed if enlarged via a caudal celiotomy. These lymph nodes are close to the medial iliac vessels; careful haemostasis and dissection are required.

Surgical complications are reported to be around 10% for anal sacculectomy alone and 12% for ones with lymphadenectomy. These include faecal incontinence (usually transient), haemorrhage, and surgical site infection. Rare complications include long-term faecal incontinence, fistulation, stricture formation and associated dyschesia.

RADIATION THERAPY

In cases where not all the tumours can be resected and have been left after surgery, the veterinary clinic will recommend radiation therpay postoperatively. To achieve long-term tumour control, the aim is to eliminate any remaining disease at the per-anal area and the associated abdominal lymph nodes.

A full course of treatment involves daily treatments of a low radiation dose for 18-19 fractions. Patients are anesthetised for a short period during the treatments. Potential side effects include skin burns and gastrointestinal signs due to radiation of the abdominal lymph node bed, which lies close to the intestines. However, most patients’ side effects are well-tolerated and typically resolve within 4-8 weeks after completion of treatment.

CONTROLLING TUMOUR SPREAD IN THE FUTURE

CHEMOTHERAPY

Chemotherapy may also be recommended postoperatively because they usually metastasise to other locations, such as regional abdominal lymph nodes and lungs. However, the effectiveness in treating anal gland tumours is unclear. Recent literature suggests using Tocenanib for stage 4 disease, and it may be helpful in some cases.

THE PROGNOSIS

Overall prognosis is good, with good reported medial survival times of over 2.8 years for unilateral and closer to two years for bilateral disease. The veterinary clinic reported negative prognostic indicators, including large tumour size (>2.5cm), nodal or distant metastasis, and hypercalcemia. Once the patient is in complete remission, we recommend repeated staging with physical examination and biochemistry to include regular ionised calcium and abdominal imaging.